When it became clear to my bosses at the international wire that I would never accept one of their many offers to be sent to the Frankfurt, I was gently encouraged to get another job.Fortunately, another unit of Dow Jones was hiring: their bond wire. There was an opening in the team covering municipal bonds, the bonds cities issue in order to finance roads, schools, and hospitals. The job was open because municipal bonds are deadly boring.

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

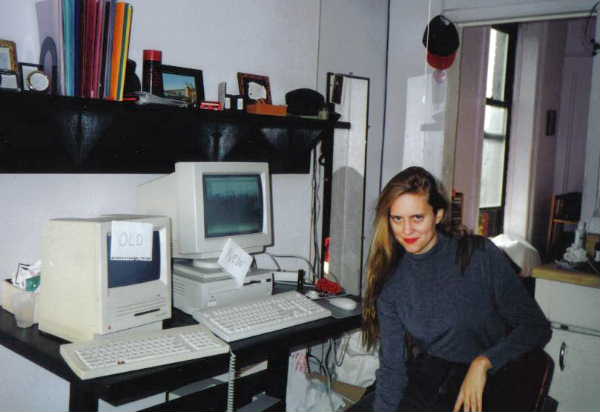

My first NYC apartment. The pig advertised a pork restaurant downstairs. Hassidics Jews, offended that the pig faced several Jewish shops across the street, threw paint bombs at it. |

Inside the apartment, a "2-rm studio" which clocked in at about 200 square feet. I had just purchased this slick new Mac Performa. |

|

|

Next: Why I never got married.

Return to Half-life homepage

Send e-mail to Xander Mellish: xmel _improved @xmel.com

U.S. Copyright Office Registration 1-141735861

Send e-mail to Xander Mellish: xmel _improved @xmel.com

U.S. Copyright Office Registration 1-141735861