|

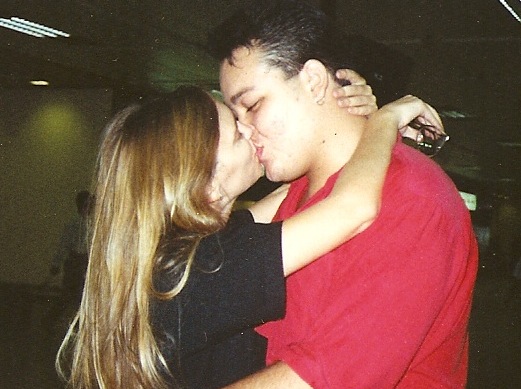

I left Hong Kong for good in June 1990, kissing my rotund, cheerful Chinese boyfriend goodbye at the airport. When I arrived back in New York, after spending a few weeks in India and a newly post-apartheid South Africa, I landed squarely in the recession of 1990. Nobody was hiring, particularly not in the media industry, and certainly not a not poorly-connected, shabbily-dressed girl with an odd foreign resume. Foreign work experience was not yet fashionable.

|  Goodbye to boyfriend. |

|

|

|

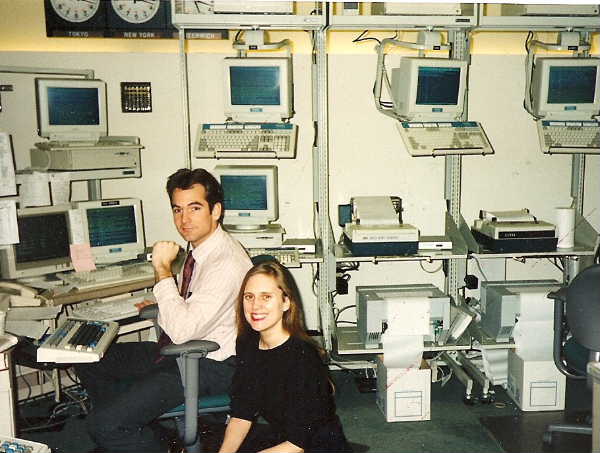

In the Dow Jones offices, with the teletypes. This fellow also kissed me, but he married one of the other reporters. |

|

|

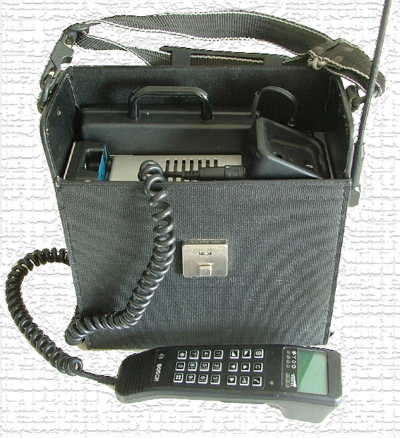

A mobile phone similar to the one I was issued in 1995. |

|

|

Next: Further adventures in journalism.

Return to Half-life homepage

Send e-mail to Xander Mellish: xmel _improved @xmel.com

U.S. Copyright Office Registration 1-141735861

Send e-mail to Xander Mellish: xmel _improved @xmel.com

U.S. Copyright Office Registration 1-141735861